Granted that we need to know history (see first post in this series) … What aspects of it do we need to study?

In my high school, history was taught as a list of dates and events. I got them stuck in my head long enough to pass the test, then forgot them. That’s an absolutely useless way to learn history.

The only effective way to study history is to look for the ideas that drive human action. On an individual scale, what you believe determines what you’ll achieve. If you think you’re helpless and incompetent, you won’t set out to establish a multi-billion-dollar company or paint a gorgeous picture.

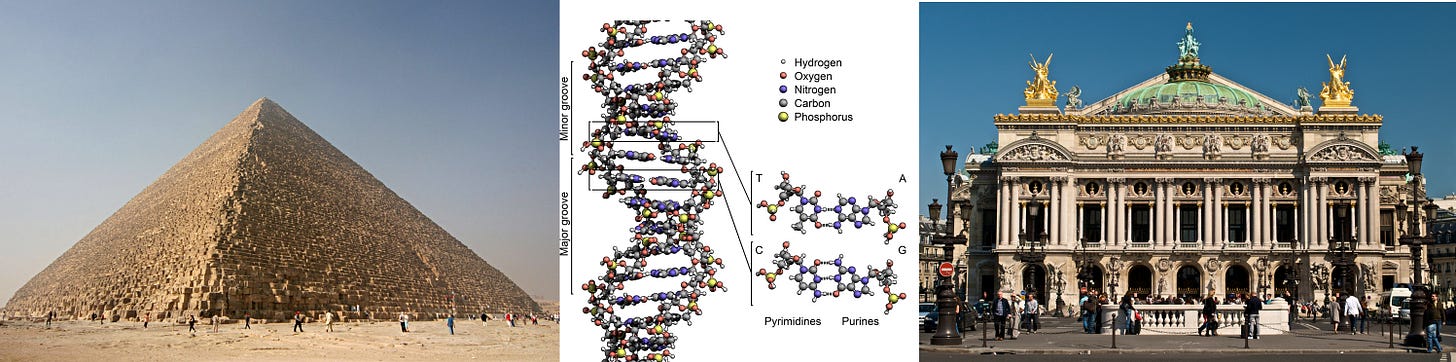

Ideas also drive human action on a large scale. Five thousand burly men can’t build a ziggurat, the Parthenon, or a DNA model, if they’re using only muscle. Someone has to conceive the project, make the plan, and supervise the execution. World-shaping accomplishments require both mental and physical effort, but the mental drives the physical.

What most people in a civilization believe drives what that civilization achieves. Suppose the dominant belief of members of the civilization is that men are helpless pawns of the gods, and that their ruler does and should have absolute control over their lives, from their jobs to whether they live or die. Most of those living in that civilization will be too cautious or too terrified to challenge the accepted order of things with new scientific theories or artistic innovations.

On the other hand, if most members of a civilization – or even a handful of its members – believe they have free will, the ability to act, the right to question and discover … Well, stay tuned to Timeline 1700-1900 to see what happens in the late 1700s.

The point is: the only effective way to learn history is to watch for dominant ideas, and then how they play out in actual events.

In the next post: History as a continuum, or why Timeline 1700-1900 is organized decade by decade.